Revolution –

Revolution –

Advanced Class

Did either side in the Irish Civil War escape manipulation into the course which most profited the British Empire? Ireland’s struggles, triumphs, and tragedies hold unique, invaluable and particularly vivid lessons for every nation

(Also see linked posts:

“Reconciliation and the Irish Civil War” Pt I & Pt II )

In the Revolutionary Decade 1913-1923, the Irish Civil War was a few months: one cataclysm, which accomplished what the British were powerless to do, with all the king’s horses and all the king’s men: it stopped the revolution in its tracks, and wiped out much of its top leadership, who’d made it all possible.

For what chance ever have the brave left captainless – what fate

but to be trampled down by the fools and cowards?

– Standish O’Grady “The Gael” 1903

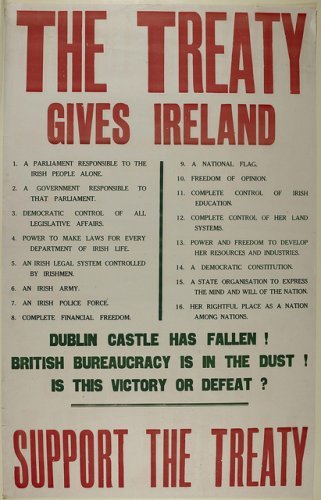

The Treaty talks of 1921 were the first between Ireland and England since the 1690s. Decades of negotiation, thankfully, followed. No one today would be called a traitor for not bringing back a 32-county republic, on their first trip to London. Nor on their tenth. Even in the most radical circles, everyone knows that would be wildly unrealistic.

We have the experience of 1922 to learn from. But the amazing achievements of Ireland’s Revolutionary Decade were won by people who had never seen a functioning democracy (as we think of it.) They wanted a republic; but had never actually done democracy. (Some might argue that the world has yet to see true democracy still.)

Michael Collins

While it was perfectly justifiable for any body of Irishmen, however small, to rise up

… against [Ireland’s] enemy… it is not justifiable for a minority to oppose

..the majority of their own countrymen, except by constitutional means.

– Michael Collins

It’s safe to say that no one expected the kind of success that Ireland won, when London sought a Truce in 1921. So no one prepared for it. Or could think out in advance how to handle it.

Cumann na mBan (Irish Volunteers women’s organization)

We didn’t think we were going to win,

and we didn’t think we were going to lose.

We just wanted to have a go.

– Vinne Byrne of The Squad

The Squad

These diverse Volunteers, ordinary men and women of all ages and backgrounds, who’d held together so valiantly in the teeth of the enemy, then fell apart at the touch of a bit of success. They let an imperfect success spoil it all. They let the enemy divide them, and were conquered. They fell to squabbling in the presence of the enemy. That dismayed Ireland, but delighted British imperialists.

These men, who nobly and successfully strove against

sea, storm, and disease, all forces beyond their control, were

ultimately overwhelmed by forces they could have,

but failed to control: their [passions].

– Captain Bligh and the Mutiny on the Bounty

Thus, in the wake of their unexpected victory, in forcing the British to the negotiating table, Ireland’s heroic insurgents tragically failed their first test as a democracy. Anti-Treaty partisans, when voted down in the June 1922 Pact Elections, refused to lay down their arms, submit to the will of the majority, and participate in the new Dublin establishment as a minority opposition, as agreed in advance, in the Collins-DeValera Pact agreement.

Would they have done so, if not for the unexpected Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson and ensuing bombardment of the Four Courts? History will never know. By then, too many risks had already been taken with Ireland’s unity. The powder keg and fuse were in place, so that any spark could set it off; even as the two sides were perhaps on their way to defuse it.

Was it entirely their fault? Collins didn’t even blame them. He knew this could happen. It’s a headly atmosphere, with no rule book. Who among us could have done better, with the same tools, knowledge, in the same time and place?

Nothing really worthwhile can be achieved in just one generation. – Thomas Cahill

“How the Irish Saved Civilisation”

It may be said that revolution, like other quixotic ventures, requires immersing oneself in a kind of unreality. For seven hundred years, Ireland had upheld the tradition of a rising in each generation. What did it take: to keep nationhood alive, through hopeless centuries of forced vassalge to a violent foreign occupation force? Through ages of famine and slavery?

Two kinds of courage enabled the nation to struggle out of bondage – the patient, enduring courage that willed survival in the long years of defeat; and the flashing, buoyant courage that struck manfully, challenging fortune.

– Florence O’Donoghue

IRA 1922 Macroom, County Cork

Know your Enemy: the far right, far left, and revolutionary failures

For the shopkeepers and farmers and clerks who made up the Irish Volunteers, this was new territory. But British Imperialists learned it all as boys, in their old-school-ties. One need only read “The Twelve Caesers” to get a clue of the arsenal of political chicanery at their command. They were the inheritors of a thousand years‘ practice in putting down popular revolts; and eliminating great popular leaders.

Likewise, the pages of revolutionary history around the world, repeatedly record the downfall of revolution arising from factions furthest to the left. Extremists, mouthing the most violently more-radical-than-thou ideology, have often enough overturned revolution, as the far right tried, but could only dream of doing.

Many in the discussion of this history might be familiar with postures today, leaning furthest to the left, and clinging to the anti-Treaty side. Some to the extent of continued rejection of any Dublin government subsequent to the Second Dail, of a hundred years ago.

Proponents of that outlook may consider themselves (not without some justice) more republican, more incisively sophisticated in their penetrating critique of British imperial policy toward Ireland, than those who accept the “official story” version of Irish history, favored by the FF-FG Dublin establishment.

At the same time, those with practical experience of anything like revolutionary struggle, (the two being not always synonymous,) may realize… that leftists with powerful opponents cannot afford to engage in loud, ugly, public quarrells among themselves. Such altercations create prime opportunities for assailants to shoot them down (figuratively or literally); and set up comrades to take the blame (if not actual bullets.)

A leader must not be unmindful of the implications of his words,

especially when speaking to people just emerging

from a great national struggle, with their outlook

and their emotions not in a normal state.

Michael Collins, 1922 – “Free St or Chaos”

“Free State or Chaos” – Michael Collins on the Treaty

A small nation, which has just victoriously beaten all odds, in an uneven struggle against vastly superior forces of a world-class imperialist war machine… cannot maintain its success by splitting in two, and taking arms against comrades; with the battle for independence only half-won.

Remember that a …fluke of politics… may fling the enthusiast Into the bosom

of the opposite party to the one which he has served all his life.

– Stendahl

British cavalry leaving Dublin 1922

The Treaty was not the disaster. The way comrades treated each other over it was the disaster.

I’d rather have one Tom Hales with me, than twelve other men. – Michael Collins

(Praising Hales, who later led the ambush where Collins died.)

It is an injustice to the memory of revolutionary Ireland’s astounding unity, in the teeth of the world’s biggest empire, that any of their descendants should immortalize their worst error: by remaining frozen in it.

The Civil War had only begun when initiatives started to bring it to an end.

– Liam Deasy, Officer Commanding, anti-Treaty Southern Division

Surely they never intended that their most questionable decisions, in their weakest moment, should be extolled as some kind of inviolable gospel, for a hundred years after! What could more break their hearts, than to see future generations rigidly adhere to the single most disastrous error, in all their stunning achievements for Ireland?

Don’t let your past dictate your future.

“A conflict of comrades.. would leave Ireland broken for generations…”

When he fell, Michael Collins was touring the country, engaging in direct, secret talks with IRA units in every region; with the express purpose of pulling the Irish Volunteers back together again. Treaty or no Treaty.

His death ended those efforts. His erstwhile comrades on the anti-Treaty side, who had been persuaded to reject the leadership which had brought them so far; who’d decided that they could do as well without him… found that they were wrong.

In 1919, Ireland’s abstention from Westminster laid the foundation for independence. But anti-Treaty abstention from Irish government, from 1922, deprived their adherents of a voice in Dublin institutions for decades after. In this, had they no part in allowing the country to be dominated, throughout its crucial formative decades, by elements who took no action to recover the partitioned North; won not a single millimeter of Irish soil from British control; sunk Ireland in one hundred years of economic and moral morass and corruption? Becoming, over the dead bodies of Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, and so many others, everything the anti-Treaty side said they were.

In short, proving James Connolly’s prophecy too true, that taking down the Union Jack and raising the Tricolor, in itself, solved none of Ireland’s problems. Dublin’s dominant political establishment has earned characterization as belonging to “those who did well out of the famine, and were determined to do even better out of the Republic.” (- J J Lee)

At the same time, credit where credit is due must be accorded the 26 county Republic of Ireland: for 100 years of massive development in flourishing, unique Irish culture, industry, education, freedoms, which would have been impossible under British rule. Dublin’s role in negotiations that ultimately brought about the Good Friday Agreement, opened the road to a more just society in all Ireland’s 32 counties; including the chance to address the unfinished business of Irish independence.

It seems easier to get the Republic from a government

working in Ireland by Irishmen than from

an Ireland under British rule.

– Jenny Wyse Power, 1922

Neither side is just black or white. It’s time to end the Civil War, as its combattants would surely have wished us to do by now. Praise the accomplishments and critique the wrongs on all sides, past, present, and in future; free from inhibition by any my-side-right-or-wrong mentality of armed camps. So that Ireland can more freely explore who we are, where we are, and where we could go from here.

R E A D M O R E

on Irish History / Irish Civil War:

“The Assassination of Michael Collins:

What Happened At Béal na mBláth?”  by S M Sigerson

by S M Sigerson

Paperback or Kindle edition here:

www.amazon.com/dp/1493784714

All other e-reader formats:

www.smashwords.com/books/view/433954

Read reviews:

http://www.rabidreaders.com/2014/12/03/assassination-michael-collins-s-m-sigerson-2/

OR ASK AT YOUR LOCAL BOOK SHOP